Stage Styles - Not All Were Coaches !

By Mary A. Helmich

Interpretation & Education Division

California State Parks, 2008

Download PDF of Article

Today the word “stagecoach” is applied almost exclusively to the classic, oval-shaped overland coach produced in Concord, New Hampshire. These have starred in countless Western movies and colored the public’s perceptions about transportation. However throughout the 19th century, there were several vehicle types used to transport passengers and mail. Each simply was referred to as the “stage.”

The kinds of stages depended largely upon the character and the condition of the roads, the distances to be traveled and their urban or rural destinations. Manufacturers produced many different styles in various sizes for stage travel. They ranged from passenger wagons and hacks to “classic” overland coaches and to open-sided wagons, including celerity wagons, mud wagons, and ambulances.

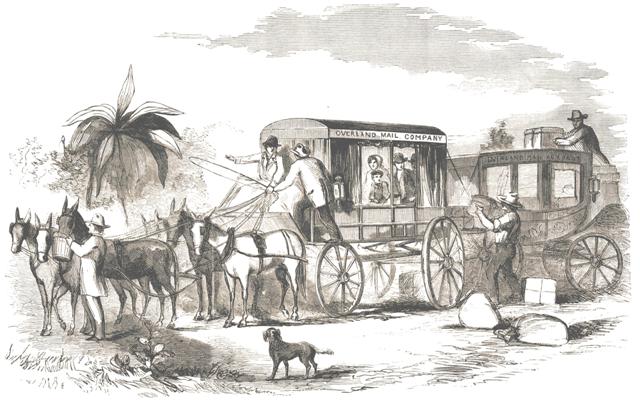

On the roughest Western roads, the Butterfield Overland Mail and later Wells, Fargo & Co. frequently transferred passengers and mail to lightweight, more durable celerity wagons or to the less expensive, but also light mud wagons.

The Butterfield Overland Mail transferred passengers and mail to light,

durable vehicles for travel over rough roads.

From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, October 23, 1858.

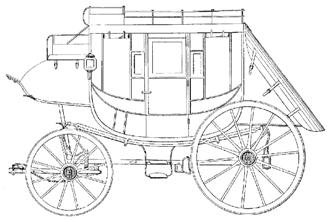

Concord Coaches

From the mid- through the late-19th century, stage vehicle manufacturing centers included Albany and Troy, New York, several towns in New England, and cities on the West Coast, like Stockton., (1) (2) Concord, New Hampshire, however, served as the center for coach production. It began when wheelwright Lewis Downing (whose shop opened in 1813) joined his skills with expert coachbuilder J. Stephens Abbot from Maine. Together they took stagecoach construction to a new level. (3) In 1826, the two began turning out their first coaches. (4) The partnership lasted over 20 years, turning into a thriving, world-renowned business.

What separated Abbot and Downing from other coachbuilders of their day were the vehicles’ handsome appearance, durability, and overall quality. (5) These masterpieces of construction had no equal. Concord stage were first to offer shock-absorbing thorough braces—an important feature not just for passengers, but for the animals pulling them, too. These braces allowed the coach to rock back and forth and swing sideways, too, providing forward momentum for the teams.

Thorough braces were strips of leather cured to the toughness of steel and strung in pairs to support the body of the coach and enable it to swing back and forth. This cradle-like motion absorbed the shocks of the road and spared the horses as well as the passengers. It also permitted the coach to work up its own assisting momentum when it was mired in a slough of bad road…These thorough braces were carefully wrought and intricate in arrangement, and it usually required the hides of more than a dozen oxen to supply enough of them for a single coach. (6)

Cross-section of the Concord Coach's thorough braces

from Nick Eggenhofer's Wagons, Men and Mules.

Mark Twain and his brother traveled west by overland stagecoach in 1861. Describing their experiences in his book, Roughing It, he wrote: “Our coach was a greate [sic] swinging and swaying stage of the most sumptuous description—an imposing cradle on wheels.” It rocked on its thorough braces, instead of bouncing on steel springs. (7)

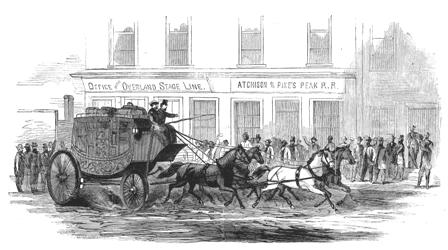

Abbot and Downing coaches came in three sizes, “…built to hold six, nine, or twelve passengers, though some of the later models could crowd in twenty. They were usually drawn by teams of four or six horses, whose harnesses were supplied by the James R. Hill Company, also of Concord.” (8) More passengers could be seated outside on top of the coach.

The Overland Mail stage departs from Atchison, Kansas.

Published in Harper's Weekly on January 27. 1866.

The company also offered special features on its vehicles.

The coaches were … equipped with an ingenious apparatus for braking. Sand boxes were placed over the brake pads in such a way so that sand could be released when approaching the more rugged hills along the trail.

The inside of the Concord Coach was only a bit over four feet in width, and its height inside was about four and one-half feet. The interior, upholstered in padded leather and damask cloth… The seats, covered with leather-covered pads, were reported to be harder than the wood beneath them….

The final touch for the Concord Coach was its paint job. And, there were never any two exactly alike. It was a gloriously beautiful coach to look at with the favorite colors for the coaches being red for the body and yellow trim, with an exquisite landscape on the doors. The two coats of paint were hand-rubbed, then finished with two more coats of spar varnish. Gold leaf scrollwork was artistically painted in the interior. (9)

1882 Dougherty Spring Wagon

Abbot and Downing produced other types of vehicles, as well.

In addition to the celebrated coaches, the firm made a variety of wagons of the more common kinds, and a wide assortment of the type of stage wagons generally known as “mud wagons.” These included models known as Passenger Wagons, Passenger Hacks, and Overland Wagons; and there was an ambulance resembling the Army’s widely-used Dougherty wagon. Open-sided wagons were designated as Mail Wagons, Australian Wagons, and Florida Wagons. A Mail Jerky was a short, two-seated wagon; and there was a Picnic Wagon, a three-seated topless open carriage. The Yellowstone Wagon, with roll-down curtains and three forward-facing seats inside, was made especially for sight-seeing in the well-known park but some were also used on regular stage runs. All these had the typical stage-wagon

thorough-brace suspension. (10)

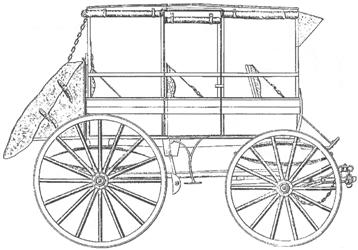

Celerity Wagons

Coach works in Albany, New York and Concord, New Hampshire (and perhaps elsewhere) manufactured celerity wagons. James Goold’s factory in Albany built 100 of the wagons for service on the Butterfield Overland route in 1857. (11) The New York Herald’s special correspondent, Waterman L. Ormsby, attributed the innovative design for the celerity wagon to John Butterfield. Instead of having a heavy wooden top, typical of most coaches, it had a light frame structure with a thick duck or canvas covering. This reduced the weight of the vehicle. Its wheels were also set further apart and were protected by wide steel rims. These details helped to keep the vehicle from tipping over or the wheels from sinking in soft roadside sands. (12)

While not as comfortable for daytime travelers as the larger, well-appointed overland coaches, they were designed for passenger travel at night. Ormsby, who was the first through passenger on the Butterfield Overland Mail Line in 1858, described the wagon’s sleeping accommodations:

As for sleeping, most of the wagons are arranged so that the backs of the seats let down and form a bed the length of the vehicle. When the stage is full, passengers must take turns at sleeping. Perhaps the jolting will be found disagreeable at first, but a few nights without sleeping will obviate that difficulty, and soon the jolting will be as little of a disturbance as the rocking of a cradle to a sucking babe. For my part, I found no difficulty in sleeping over the roughest roads, and I have no doubt that any one else will learn quite as quickly. A bounce of the wagon, which makes one’s head strike the top, bottom, or sides, will be equally disregarded, and “nature’s sweet restorer” found as welcome on the hard bottom of the wagon as in the downy beds of the St. Nicholas. White pants and kid gloves had better be discarded by most passengers. (13)

A Concord-made Celerity Wagon exhibited at Seeley

Stable in Old Town San Diego State Historic Park.

Abbot and Downing’s version of the celerity wagon, produced in Concord, used thorough braces (described in the previous section), which made the ride more comfortable for passengers and far safer for the animals pulling the vehicle. It also was smaller, having two passenger seats. And, it probably was more maneuverable on mountain roads and across deserts. According to Nick Eggenhofer, it could carry five to six hundred pounds of mail. (14) Because of the light roof construction, baggage was stowed in the boot at the back of the vehicle or, if need be, inside with the passengers, but not on top. Wide window and door openings also kept the celerity wagon lightweight, letting the air flow through along with the dust and the rain. Heavy duck or leather roll-down curtains were the passengers’ only protection from the elements.

There was no way to heat the stage.

Mud Wagons

One of the most common and preferred stage vehicles used in the West by stage operators was the mud wagon. Its less than flattering name may offer a hint as to the character of the passenger experience. While a celerity wagon could be considered a mud wagon, because of its lightweight construction and use over rough roads, not all mud wagons were celerity wagons. Some were wagonettes, distinguished by their square, boxy design. Christine Jeffords described them in her article, “Here She Comes! The Stagecoach”:

A square-bodied, homely conveyance with a top of treated canvas stretched over wooden struts, it lacked the Concord's beautifully curved and joined panels, being enclosed only halfway up by flat panels decorated with a roving of wood strips to make it look more expensively made. Its carriage and running gear were lighter than the Concord's, but still sturdy enough for slower travel over muddy roads, and it had the same sort of thoroughbraces as the big one. When its canvas side-curtains were rolled up and fastened, it was almost completely open, which let in more dust but also admitted every available breeze—an advantage in the Southwest. Built like its big brother by Abbott & Downing, it was tough and durable, but lighter in weight, and had a lower center of gravity, making it good for mountain roads, such as those routinely servicing mining camps. The body measured from 6'10" to over 8' high, the track 5'2" (in the U.S.) or 4'8" (in Canada), and it weighed from 800 lb. (for the commonest nine-passenger model) to 1200 (for a 14-). It had two to three inside seats (no roof passengers), and baggage was stored in the single rear boot or piled inside with the passengers. (15)

Unlike the classic Concord stagecoaches, which could be mired in bad weather, mud wagons—true to their name—could travel over trails and roads during inclement weather. However, the only protection provided for passengers against bad weather and dusty roads were the canvas side-curtains, which could be rolled down and fastened.

These vehicles cost about 35% what the Concord did, but the later varieties became beautiful, with curved panels in the rove sides, sometimes solid sides and doors and/or permanent tops with railings, or curved dashes and elaborate leather trim. (16)

The Wells Fargo Mud Wagon displayed in Old Town San Diego State Historic Park’s Seeley Stable once traveled the rugged roads between San Diego and Julian. The vehicle was given to the park by Roscoe E. Hazard in 1972. There are three seats inside with a luggage rack on top. The vehicle has not been restored. Today, more than 100 years later, it retains its worn but original finishes that give an indication of its hard use on the dusty roads of San Diego County.

Variations in mud wagons were made by different manufacturers. Note the differences in the Northern Trinity Stage Co.’s vehicle produced by M.P. Henderson & Son in Stockton. It was used on the steep and rugged roads of Northern California. The stage is displayed at Shasta State Historic Park.

Left: The Wells Fargo Mud Wagon exhibited in

Seeley Stable, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park.

Right: The Northern Trinity Stage, built by M.P. Henderson & Son in Stockton, California,

on display at Shasta State Historic Park.

Find Stagecoaches on Exhibit Throughout the State

(1) Josiah Gregg in his Commerce of the Prairies published in 1884, also mentions Dearborn carriages and Jersey wagons.

(2) Henderson & Co. out of Stockton, California built mud wagons used by the Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Co. R.D. Israel and John Van Alst operated a carriage manufacturing business in Old Town San Diego.

(3) Nick Eggenhofer, Wagons, Mules and Men: How the Frontier Moved West. Hastings House Publishers,

New York, 1961. P.151.

(4) David Nevins, The Expressmen, The Old West, Time-Life Books, New York, 1974. P.134.

(5) Eggenhofer, Ibid.

(6) Peter Anthony Adams, “Abbot-Downing Concord Coaches,” http://theconcordcoach.tripod.com/abbotdowning/index

(7) Mark Twain, Roughing It, A publication of the Mark Twain Project of The Bancroft Library. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1995. P. 7..

(8) Adams, Ibid.

(9) Adams, Ibid.

(10) Eggenhofer, pp. 151-152.

(11) Jim W. Adams, “The Butterfield Overland Stagecoach through Guadalupe Pass,” Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

www. geocities.com/guadalupemountains2/history.pdf. P. 326.

(12) Vernon H. Brown, “American Airlines Along the Butterfield Mail Route,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, c.1954. P. 10

http://digital.library.okstate.edu/Chronicles/v033/v033p002.pdf

(13) Waterman L. Ormsby, The Butterfield Overland Mail, ed. Lyle H. Wright and Josephine M. Bynum, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, 1942. P..

(14) Eggenhofer, P.156.

(15) Christine Jefford, "Here She Comes ! The Stagecoach." http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~poindexterfamily/ChristinesPages/Stagecoach.html

(16) Ibid.