Recent Archaeological Investigations at the Stonewall Mine Site

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, San Diego County

by

Michael Sampson, Associate State Archaeologist (Retired)

Contributions by Rachel Ruston and Don C. Perez, Archaeological Specialists

Southern Service Center, California State Parks

Introduction

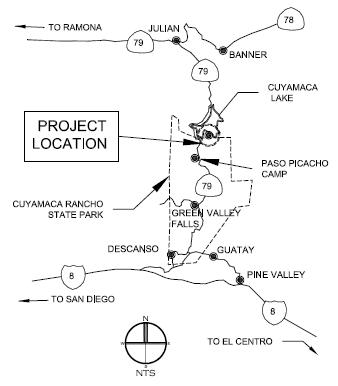

The remains of the nineteenth century Stonewall Mine and its former workers’ community are located at the northern end of Cuyamaca Rancho State Park (SP), San Diego County, next to Cuyamaca Lake (Figure 1, below). Together, they are designated archaeological site CA-SDI-18502. The site is open to the public daily and has a parking lot, restroom, and picnic tables. Archaeologists from the Southern Service Center (SSC) of California State Parks conducted test-level archaeological excavations at potential locations of new park visitor facilities in April-June 2006 and October-November 2007 to identify the presence or absence of significant cultural remains. The latter fieldwork represents the first subsurface archaeological explorations ever conducted at the Stonewall Mine site.

The geomorphic province in which Cuyamaca Rancho SP lies is composed primarily of granitic rock of the Southern California Batholith. The batholith has been dated as Late Cretaceous in age. The Stonewall Mine itself consists of a body of gold-bearing quartz surrounded by quartz diorite and schist. Today, the site is characterized by a pine-oak woodland vegetation community with a ground cover dominated by exotic grasses. Cuyamaca Lake and montane meadows surround Stonewall Mine and the old townsite.

View Project Maps (Figure-1) PDF

Figure 1: Stonewall Mine Project Location

Previous Archaeological Fieldwork

California State Parks staff, directed by the late State Historian John McAleer, conducted a detailed archaeological and historical study of Stonewall Mine and the associated townsite of Cuyamaca in 1982. This work, which involved no archaeological excavation work, was reported in a thoroughly researched 1986 report. A total of 221 separate cultural features, divided into ten principal categories, were recorded and measured during the 1982 fieldwork. [Note: the term “feature” used here refers to physical evidence of historic-period buildings, structures, trails, artifact concentrations, and similar cultural remains.] The categories consisted of flats (primarily, building remains), prospect holes or mining depressions, trenches, mounds or mine tailings, roads, trails, artifacts, trash deposits, and “large areas” (features of expansive areal extent). Subsequent archaeological studies by SSC Archaeologists have defined an additional 18 historic features at the Stonewall Mine site. No significant prehistoric cultural remains have been found within the 2006 and 2007 Stonewall Mine project area.

History (Based primarily on research by H. John McAleer and Alexa Luberski-Clausen)

The discovery of the gold ore deposits of the Stonewall Mine is a matter of some debate. There is agreement that the gold discovery occurred in March 1870 and mining within the present-day park began soon thereafter. Ownership of the Stonewall Claim became the subject of litigation, though, by early 1871, A. P. Frary and J. M. Farley had purchased all claims to the Stonewall Mine and had a full mining operation in place; the remains of the 1870s mine shaft is located north of the later (1886-1892) mine shaft. Frary and Farley sold their mine holdings in January 1876 to settle financial difficulties. The Stonewall Mine reopened in early 1885, but, by September 1886 the mine was sold again to Robert W. Waterman, who had been successful in previous mining ventures. Subsequently, Waterman purchased lands of the Rancho Cuyamaca Grant; this grant land comprises the present-day state park. Waterman was elected Lieutenant Governor of California in 1886 which led him to turn over supervision of the mine to his son, Waldo. In 1887, Waterman became Governor when the incumbent governor died. Stonewall Mine had many successful years under Waterman’s ownership; Waldo Waterman, Robert’s son, served as Mine Superintendent during these good years. Waldo, with a degree in mining engineering from UC Berkeley, directed the day-to-day operations of the mine and served as overseer of the Rancho Cuyamaca Grant lands.

Figure 2: Stonewall Mine 1889 or 1890, with Hoist House and Mill Buildings

Stonewall Mine (Figure 2, above) was well publicized as a highly successful mining operation by 1886. Gold production at the mine continued to be strong throughout 1886, 1887 and 1888 under Waldo’s direction. For example, 5,182 tons of gold ore was mined and processed in 1888 with a total value of $198,666. In 1889, Waldo directed the construction of a new 20-stamp mill that was added to the existing 10-stamp mill. Reportedly, a total of 300,000 bricks were made on-site for use in the new stamp mill. In this same year, the work force reached 200 men and the mine had been sunk to a depth of 400 feet. The mine shaft, identified as Feature 81, reached a depth of 600 feet in 1892. Stonewall Mine under Waterman’s ownership ended production by mid-1892. Total gold ore production from 1888 to 1892 (first three months) was 57,754 tons with a dollar value of $906,063. According to a 1963 California Division of Mines & Geology report, Stonewall Mine was the most productive gold mine in current San Diego County with a total yield of approximately two million dollars over its entire span of operation. [Note: San Diego County was much larger than today up to 1907.]

During the operation of Stonewall Mine, a lively community for the mine workers and families was located nearby in the present-day State Park. The community of Cuyamaca consisted of two bunkhouses for single miners, cabins for married workers, a boarding house (that sometime in 1891 became a hotel), the Superintendent’s house, a school, a library, a general store, a cemetery, and support structures.

Robert Waterman had passed away in 1891, a year after leaving the Governor’s office. Sather Banking Company became owner of Stonewall Mine and holdings of adjacent lands by the latter part of 1892 to satisfy financial claims against the Waterman Estate. The workers’ community became a resort for several years after the mining operation ended, until the early 1900s.

An option to reprocess the tailings of Stonewall Mine stamp mill were apparently purchased in 1898 by a company called Strauss and Shin from Sather Banking Company, the land owners. The Strauss and Shin operation sought to extract gold from the tailings left from the Stonewall Mine operation that ended in 1892 using the relatively new cyanide process. Experiments with the use of cyanide to extract gold took place in many countries throughout the 1880s, but, this technique only proved to be commercially successful as a gold processing technique in 1890. An economically viable cyanide processing technique was introduced to the United States shortly afterwards.

According to a San Diego Union newspaper article dated March 14 1899, the Strauss and Shin operation included the construction of “several large buildings,” with “one containing the tanks being 200 feet long and 60 feet wide, and another containing the cyanide plant being 40 by 60 feet.” The March 14, 1899 article reported that the buildings had been completed the previous week, and “about twenty men” had begun working on the tailings that week. A photograph of the operation from the San Diego Historical Society collections (Figure 3, below) clearly shows a large-sized building (Feature 177), used in the cyanide processing, and a tramway leading up to it from next to the abandoned hoist building (Feature 81).

Figure 3: Stonewall Mine Cyanide Building, circa 1899-1901. Note the tailings spilling out

from the building; the hoist building for the abandoned mine is at right.

Photo courtesy of San Diego Historical Society)

According to a 1963 California Division of Mines & Geology report, the Stonewall Mine cyanide reduction plant operating from 1898-1901 processed a total of 35,000 tons of tailings and they reportedly yielded an average of $4 to $6 of gold per ton. Another source indicates that the cyanide operation at Stonewall Mine yielded a total of $50,000, a figure not consistent with the average yield identified in the 1963 report.

The land of Rancho Cuyamaca Grant stayed in the ownership of the bank until 1917 when Capitalist Colonel A. G. Gassen bought the mine and grant lands. Los Angeles Businessman Ralph Dyar acquired the land of the present-day state Park, including, Stonewall Mine, in 1923. Dyar sold off the mine buildings and filled-in the main Stonewall Mine shaft soon after purchasing the land. California State Parks purchased Rancho Cuyamaca in 1933 and it became known as Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a Depression-era Federal works program for young men, constructed many facilities within the new park in the 1930s, including parking and a picnic area at Stonewall Mine. The CCC then constructed a Girl Scout Camp on the edge of the mine and the townsite of Cuyamaca. The camp included a lodge, restrooms, a swimming pool, storage, and camping tents for the scouts. The reservoir (Feature 180), originally built to supply water for Stonewall Mine and miners community, was renovated by the CCC for use by the scouts. The Girl Scouts stopped using the camp in 1975, and then the camp buildings were removed. The 2003 Cedar Fire destroyed all wood members of the historic reservoir, the only remaining standing historic structure from Stonewall Mine.

Fieldwork Methods and Results

The potential locations for proposed day-use park facilities dictated the archaeological work locations for the 2006 and 2007 SSC investigations at Stonewall Mine. However, the site areas examined were diverse in historic function and content. Ultimately, the SSC fieldwork tested portions of several historic features associated both with the Waterman era mining (1986-1892) and the subsequent cyanide reprocessing operation (1898-1901). The methods and results of these efforts are described in excavation reports.

The excavation units in 2006 and 2007 were dug in stratigraphic levels, that is, by following natural and culturally-deposited layers of soils and sediments. All excavated materials were dry-screened through eighth-inch and quarter-inch hardware cloth to ensure recovery of artifacts and subsistence remains. Standard professional archaeological fieldwork techniques and tools were employed during the above-cited test excavations at Stonewall Mine. The testing in 2006 and 2007 employed units of varying sizes, shovel test pits, and surface collections at specific locations. The artifact collection will be stored at the Begole Archaeological Research Center in Borrego Springs, a facility operated by Colorado Desert District staff of California State Parks.

A ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey was conducted by staff from ASM Affiliates, a cultural resources consultant firm in Carlsbad, at the beginning of the 2007 archaeological test excavations. The GPR instrument can reveal buried items, including, potentially significant cultural features that are otherwise not visible on the surface. This instrument does not interpret those subsurface findings, but, archaeologists use GPR to help focus excavations to particular locations. The GPR transects and grids by the ASM staff were clearly marked on-site making it easy for the archaeological field crew to place excavation units within the surveyed areas. The GPR report is on file at the Southern Service Center.

Other investigations were accomplished at the Stonewall Mine project site by the SSC archaeologists in addition to the test excavations. Historic mining features, in particular, tailings piles, found next to the mine shaft and stamp mill were examined, photographed, and mapped by GPS. SSC archaeologists conducted an examination of the site of the Girl Scout Camp swimming pool, where the existing restroom, picnic area, and access path are located, to document the Civilian Conservation Corps era landscape features.

Selected portions of two structural features associated with the Waterman-era Blacksmith Shop (1886-1892) and features from the subsequent cyanide processing operation (1898-1901) were investigated in 2006. Four new cultural features were defined during the 2006 study that provided additional details about the cyanide works. During the 2007 fieldwork, additional testing occurred within the Blacksmith Shop site, as well as, work at two Waterman period structural flats and within a large area of tailings (Figure 4, below). [Note: “Tailings” represent the waste product from the stamp mill after the ore is crushed and the gold has been extracted from it.]

Figure 4: Exhibit Building and Feature 86 in foreground; Waterman-era mine

shaft in background, view to west/southwest. Photo taken October 1, 2007.

The spring 2006 archaeological fieldwork at the Stonewall Mine site provided strong evidence for preserved significant structural remains related to the 1898-1901 cyanide reprocessing operation. A series of shallow rectangular depressions with intervening earthen mounds, for example, are consistent with descriptions of percolation vats provided in an 1894 California State Mining Bureau publication. A concentration of historic artifacts collected during the 2006 fieldwork, such as, consumer goods, kitchen items, clothes parts, a stove part, other domestic debris, bricks, and structural cuts into the slope at the west end of one feature provide good evidence that a modest-sized residence for the cyanide operation worker had been located here. Evidence of additional structures associated with the cyanide operation included flattened terrain that had been cut into the slope; these structural flats also contained window glass, nails, remnants of corrugated sheet metal, and other material. One large-sized cultural feature that measures 3.2 acres consisted of reprocessed mine tailings (gold ore crushed to a fine powder consistency in a stamp mill), a holding pond, channel, and earthen berm or dam (Figure 5). This feature is interpreted as both part of the mechanism by which the used cyanide solution was recaptured for reuse and the final resting place of the spent, reprocessed tailings.

Figure 5 : Overview of Stonewall Mine site, photo 4-18-06. Tailings piles

remaining from the 1899-1901 cyanide reprocessing operation

are visible at tree line (arrow).

The nail assemblage was a particularly noteworthy finding from the investigations at Stonewall Mine. The abundance of nails, nail fragments, the presence of nail plate fragments, and the high variability in nail style and size from Feature 84 in 2006 and 2007 test excavations indicated that nails were made at the Blacksmith Shop for the specific needs at Stonewall Mine. The remote location of Stonewall Mine suggested that the most efficient means to get nails suitable to the needs at the mine would be to make them on-site. This same conclusion can be applied to other tools and the bricks used at Stonewall Mine and mill. There is not an abundance of large nails or spikes in our collection. Few large nails were recovered (3 square spikes and 15 round). This may be due to the fact that all of the structures formerly present at the site had been removed in the 1920s, and the building materials and hardware were probably salvaged for other projects. Mining tools and machine parts would also have been repaired on-site, as evidenced in our fieldwork results.

Historical documents, in particular, the Waterman Letters, indicated thousands and thousands of bricks had been manufactured at the Stonewall Mine site for use in building construction. One of our 2007 excavation units yielded a sizable component of broken bricks, which prompted us to attempt a study of them. Our analysis, conducted by SSC Archaeologist Don C. Perez, showed that a majority of the analyzed bricks were hand-made using a soft-mud technique by non-professional brick makers with limited access to high-quality materials. Such an outcome would be expected where bricks were opportunistically manufactured from raw materials readily available near the mine, and not obtained from a brick manufacturer.

A significant number of the excavation units and shovel test pits yielded abundant Julian schist waste rock. Apparently, a traditional practice among mines in the western United States included placing waste rock immediately outside the mine opening and then these piles were graded flat. The graded waste rock deposits could be utilized in the continuing operation of the mine. At Stonewall Mine, the flattened waste rock deposits became areas to store equipment and places to construct new mine buildings as production expanded.

Stonewall Mine is a highly significant cultural property that has much to inform us about historical issues such as, mining in our local mountains, the everyday work and life of a miner, the effects of gold mining on local settlement, mining technology in the late 19th century, brick making technology in the late 19th century, archaeological signatures of cyanide reprocessing, fuel use at mining operations and its effects upon local forest lands, and other issues. The site is today preserved for posterity, open to the park visitor, and protected by State Parks Ranger and Maintenance staff.

Acknowledgements

Michael Buxton, Kyle Knabb, Soraya Mustain, and the present writer conducted the 2006 fieldwork at the Stonewall Mine site. Kyle and Soraya efficiently performed most the lab work for the 2006 project and prepared the tables for the 2006 report. Michael Buxton, Matt Mandich, Don C. Perez, Erin Smith, and the present writer conducted the 2007 fieldwork. Rachel Ruston skillfully performed the lab work and much of the artifact analysis for the 2007 study at Stonewall Mine. Marla Mealey provided much appreciated technical support to the two projects. The present writer, Michael Sampson, directed the fieldwork and lab work for the two projects. The historical background for Stonewall Mine was the result of earlier research by Alexa Luberski-Clausen, John McAleer, Tom Crandall, and Leland Fetzer.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, William Hampton

2002 Machine Cut Nails and Wire Nails: American Production and Use for Dating 19th-Century and Early-20th-Century Sites. Historical Archaeology 36(4):66-88

Ayres, James E., A.E. Rogge, Everett J. Bassett, Melissa Keane, and Diane L. Douglas

1992 Humbug! The Historical Archaeology of Placer Mining on Humbug Creek in Central Arizona.

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Phoenix.

Becker, Mark S.

2007 The Results from a GPR Investigation of Stonewall Mine (CA-SDI-18502) in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, California.

Report on file, California State Parks, San Diego.

Black, Art

1986 An In-Progress Study of Cut Nails. Paper Presented at 1986 Society for Historical

Archaeology Annual Meetings, Sacramento.

Burney, Michael S., Stephen R. Van Wormer, Claudia B. Hemphill, James D. Newland, William R. Manley, F. Paul Rushmore, Susan D. Walter, Neal H. Heupel, Jerry Schaefer, and Lynne E. Christenson

1993 The Results of Historical Research, Oral History, Inventory and Limited Test Excavations Undertaken at the Hedges/Tumco Historic Townsite, Oro Cruz Operation, Southwestern Cargo Muchacho Mountains, Imperial County, California. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Carrico, R. L.

1986 Before the Strangers: American Indians in San Diego at the Dawn of Contact. Cabrillo Historical Association,

San Diego, California.

Cline, Lora

1979 The Kwaaymii: Reflections on a Lost Culture. Occasional Paper No. 5. IVC Museum Society, El Centro, California.

1984 Just Before Sunset. LC Enterprises, Tombstone, Arizona.

Drucker, Philip

1937 Culture Element Distributions V: Southern California. University of California Anthropological Records 1(1):1-52.

Elsasser, Albert B.

1978 Basketry. In California, edited by Robert F. Heizer, pp. 626-641. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8, W.C. Sturtevant, general editor, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fetzer, Leland

2002 A Good Camp: Gold Mines of Julian and the Cuyamacas. Sunbelt Publications, San Diego.

2006 Governor Robert W. Waterman, Waldo Waterman, and the Stonewall Mine, 1886-1891.

The Journal of San Diego History 52(132): 44-61.

Fontana, Bernard L. and J. Cameron Greenleaf

1962 Johnny Ward’s Ranch: a Study in Historical Archaeology. The Kiva 28 (1-2):1-115.

Foster, Daniel G.

1981 A Cultural Resources Inventory and Management Plan for Cuyamaca Rancho State Park,

San Diego County, California. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Gifford, Edward. W.

1931 The Kamia of Imperial Valley. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 97. Washington.

Godden, Geoffrey A.

1964 Encyclopaedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks. Bonanza Books, New York.

Guerrero, Monica

2001 Hual-Cu-Cuish: A Late Prehistoric Kumeyaay Village Site in the Cuyamaca Rancho State Park,

San Diego County, California. Master’s Thesis, Department of Anthropology, San Diego State University.

Gross, G. Timothy and Michael Sampson

1990 Archaeological Studies of Late Prehistoric Sites in the Cuyamaca Mountains, San Diego County, California.

In Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology, Volume 3: 135-148.

Gurcke, Karl

1987 Bricks and Brickmaking: A Handbook for Historical Archaeology. University of Idaho Press, Moscow, Idaho.

Hardesty, Donald L.

1988 The Archaeology of Mining and Miners: A View from the Silver State. Society for Historical Archaeology,

Special Publication Series, Number 6.

Hedges, Ken, and Christina Beresford

1986 Santa Ysabel Ethnobotany. San Diego Museum of Man Ethnic Technology Notes. No. 20. San Diego, California.

Hines, Phillip

1994 Archaeological Testing and Monitoring for the Green Valley Campground Rehabilitation Project,

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Kroeber, Alfred L.

1970 Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 78.

Larrabee, Edward McM.

1961 Archaeological exploration of the court house building and square, Appomattox Court House

National Historic Park. Ms. On file, Mid-Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, Philadelphia.

Lockhart, Bill

2006 The Color Purple: Dating Solarized Amethyst Container Glass. Historical Archaeology 40(2):45-56

Luberski, Alexandra Helen

1984 Governor Robert Whitney Waterman, 1887-1891: California’s Forgotten Progressive.

Master’s thesis, Department of History, San Diego State University.

Lucas, Carmen

1995 Reconstructing the Ethno-History of the Kwaaymii of the Laguna Mountain San Diego County California.

Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Southern Service Center, San Diego, California.

Luomala, Katherine

1978 Tipai and Ipai. In California, edited by Robert F. Heizer, pp.592-609. Handbook of North American Indians,

Vol. 8, W.C. Sturtevant, general editor, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

McAleer, H. John

1986 Historic Overview. In Stonewall Mine and Cuyamaca City, A Historical and Archaeological Investigation of

Southern California’s Largest Gold Mine, compiled by H. John McAleer, Donald Storm, and Joe Hood, pp. 2-58.

California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

McAleer, H. John, Donald Storm, and Joe Hood

1986 Stonewall Mine and Cuyamaca City, A Historical and Archaeological Investigation of

Southern California’s Largest Gold Mine. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

McDonald, Alison Meg

1992 Indian Hill Rockshelter and Aboriginal Cultural Adaptation in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park,

Southeastern California. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Riverside.

Mealey, Marla M.

2004 Post-Fire Archaeological Site Assessment Report for Portions of the Cedar Fire Burn Area Within

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

2005 Post-Fire Archaeological Site Assessment Report for Portions of the Cedar Fire Burn Area Within

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, Part II. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Munsey, Cecil

1970 The Illustrated Guide to Collecting Bottles. Hawthorn Books, Inc., New York.

Nelson, Lee H.

1968 Nail Chronology as an Aid to Dating Old Buildings. American Association for State and

Local History Technical Leaflet 48.

Parkman, E. Breck (Editor)

1981 A Cultural Resources Inventory and Management Plan for Prescribed Burning at Cuyamaca Rancho State Park,

San Diego County, California, Volume II. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Philbin, Tom

1978 The Encyclopedia of Hardware. Hawthorn Books, Inc., New York.

Piwarzyk, Robert

1996 Firebricks. In The Laguna Limekilns: Bonny Doon. pp. 64-69. <http//www.santacruzpl.org/work/limefire.shtml>

Accessed January 25, 2008.

Praetzellis, Mary (editor)

2004 SF-80 Bayshore Viaduct Seismic Retrofit Projects Report on Construction Monitoring, Geoarchaeology,

and Technical and Interpretive Studies for Historical Archaeology. Report on file at California Department of

Transportation District 4, Oakland.

Preston, E.B.

1890 San Diego County. In 10th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, California State

Mining Bureau, pp. 540-544. Sacramento.

Rensch, Hero Eugene

1953 Chronology of the Stonewall Mine. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Rogers, Malcom J.

1936 Yuman Pottery Making. San Diego Museum Papers, No. 2. Ballena Press, Ramona, California.

Sagstetter, Beth and Bill

1998 The Mining Camps Speak: A New Way to Explore the Ghost Towns of the American West.

BenchMark Publishing of Colorado.

Sampson, Michael P.

2006 Archaeological Tests Within the Stonewall Mine for the ADA Improvements Project, Cuyamaca Rancho State Park,

San Diego County. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Sampson, Michael

2008 Archaeological Manifestations of Cyanide Reprocessing at the Nineteenth Century Stonewall Mine,

San Diego County. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for California Archaeology, Burbank.

[Manuscript on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.]

Sampson, Michael and Rachel Ruston

2008 The 2007 Investigations for the Stonewall Mine for the ADA Improvements Project,

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Shipek, Florence

1970 The Autobiography of Delfina Cuero: A Diegueño Indian. Malki Museum Press, Banning, California.

1981 A Native American Adaptation to Drought: The Kumeyaay As Seen in the San Diego

Mission Records 1770-1798. Ethnohistory 28(4):295-312.

1986 The Impact of Europeans upon the Kumeyaay. Cabrillo Historical Association, San Diego, California.

Spier, L.

1923 Southern Diegueño Customs. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and

Ethnology 20(16):297-358.

Storm, Donald, Joe Hood, H. John McAleer

1986 Field Findings. In Stonewall Mine and Cuyamaca City, A Historical and Archaeological Investigation of

Southern California’s Largest Gold Mine, compiled by H. John McAleer, Donald Storm, and Joe Hood, pp. 65-113.

California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Teague, George A.

1979 Reward Mine and Associated Sites, Historical Archaeology on the Papago Reservation.

Western Archaeological Center Publications in Anthropology No. 11.

Thornton, Sally Bullard

1987 Daring to Dream: The Life of Hazel Wood Waterman. San Diego Historical Society, San Diego.

Toulouse, Julian Harrison

1971 Bottle Makers and Their Marks. Thomas Nelson, New York.

True, D. L.

1961 Archaeological Survey of Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, San Diego County, California.

Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

1970 Investigation of a Late Prehistoric Complex in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, San Diego County, California.

Archaeology Survey Monograph, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Tsunoda, Koji

2005 GIS-Based Archaeological Settlement Pattern Analysis at Cuyamaca, San Diego County, California.

Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, San Diego State University.

University of Utah

1992 Intermountain Antiquities Computer System User’s Guide (IMACS), Nails section, Part 470.

University of Utah, Salt Lake City <http://www.anthro.utah.edu/labs/imacs.html>

Van Wormer, Stephen R.

1996 Revealing Cultural Status and Ethnic Differences Through Historic Artifact Analysis.

In Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology, Volume 9: 310-323

Vogel, Michael

1995 In Up Against the Wall: An Archaeological Field Guide to Bricks in Western New York.

<http//www.buffaloah.com/a/DCTNRY/mat/brk/brickyda.html> Accessed January 25, 2008.

Walker, John W.

1971 Excavations of the Arkansas Post Branch of the Bank of State of Arkansas. National Park Service,

Southeast Archaeological Center, Ocmulgee, Georgia.

Waterman Papers, Stonewall Mine Collection

1886-1893 Select papers from the Robert Whitney Waterman Collection, Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley.

Correspondence and mining company records culled from the greater collection by Thomas Crandall for

California State Parks Department. Manuscript on file, California State Parks, Southern Service Center,

San Diego, California. Seven Bound Volumes.

Weber, F. Harold

1963 Geology and Mineral Resources of San Diego County, California. California Division of Mines and Geology,

County Report 3. San Francisco.

Woodward, Lucinda

1981 Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, An Overview of Its Euroamerican History. In A Cultural Resources Inventory and

Management Plan for Prescribed Burning at Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, San Diego County, California,

Volume II, edited by E. Breck Parkman, pp. 49-115. Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Young, Otis E., Jr.

1970 Western Mining: An Informal Account of Precious Metal Prospecting, Placering, Lode Mining, and Milling on the

American Frontier from Spanish Times to 1893. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.