By Blaine P. Lamb (Retired)

Cultural Resources Division

“The emigrants by the Gila route gave a terrible account of the crossing

of the Great Desert, lying west of the Colorado. They described this region as

scorching and sterile -- a country of burning salt plains and shifting hills of sand,

whose only signs of human visitation are the bones of animals and

men scattered along the trails that cross it.” (1)

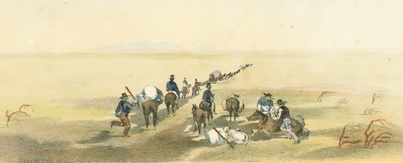

Pioneer travel correspondent Bayard Taylor made this observation in 1849 as thousands of adventurers on the southern trails to the California gold fields crossed the desert country between the Colorado River and the coastal mountains. Their experience challenged both their imagination and their stamina. Even after traversing the deserts of New Mexico, Arizona and Sonora, travelers from the humid east had trouble comprehending the aridity and starkness of this entrance to California. Few had anything positive to say about the experience, and wrote off the land as utterly desolate and uninhabitable, a purgatory to be crossed as quickly as possible. This paper examines the last leg of the southern route to West Coast in the mid-nineteenth century through the Colorado Desert of southeastern Alta California and northeastern Baja California.

Flat, dry and mercilessly hot in summer, most of the Colorado Desert lies at or below sea level, with two features defining the region. The first, the Salton Sink, was a vast salt plain with a briny marsh in its center, into which a flooding Colorado River occasionally drained (the last inflow in 1905-1907 creating today's Salton Sea). It served as a barrier to travelers wishing to take north-south or east-west transits across southeastern California.

Roughly southeast of the Salton Sink lies the second determining feature in the history of the Colorado Desert, the Algodones Sand Dune System. These ever-shifting mountains of sand stretch southeastward across the border into Mexico and blocked most direct east-west travel from the Colorado River crossing at Yuma, forcing trails, and later roads, irrigation canals and railroads to detour into northern Baja California.

Today, the heart of the Colorado Desert comprises the lush green Imperial and Mexicali Valleys, testaments to what can be done with enough water, money and political will. One hundred and fifty years ago, however, green was a color found largely in the abstract on the Colorado Desert. Sand, creosote, mesquite and waterless blue skies were the dominant factors of life there, and yet for centuries the Cauhilla, Kumeyaay and Quechan peoples had inhabited this harsh region. In 1771, Father Francisco Garces, on a solitary expedition from Mission San Xavier del Bac near Tucson, crossed the Colorado Rivernear its mouth and wandered into the Colorado Desert from the south. He encountered the channel of the New River and continued to the northwest until he could make out a gap leading into the coastal mountains. The following year, Lieutenant Pedro Fages entered the Colorado Desert from the west in pursuit of Indians fleeing the San Diego Mission. His expedition ventured out onto the desert plain but failed to find any sources of water and turned back. (2) (3)

The exploits of Fr. Garces and Lt. Fages stimulated Spanish interest in an overland route connecting the frontier provinces of northern Mexico with Alta California. Juan Bautistade Anza, accompanied by Fr. Garces, opened the route in 1774 and 1775. His first expedition left Tubac, Arizona, and crossed the Colorado below its confluence with the Gila. Anza marched southward along the Colorado, avoiding the sand dunes, and then turned west and north enroute to Mission San Gabriel. Anza's second expedition from Arizona, consisting of colonists to settle San Francisco, crossed the Colorado at Yuma, and, after again skirting the dunes, divided into three columns for the trek across the desert. The columns met near the Carrizo-San Felipe Creek confluence, and then ascended the coastal mountains. (4) Anza's success convinced Spanish authorities of the feasibility of an overland link between Sonora and Alta California. To strengthen their hold on the route, the Spanish developed a permanent outpost on the eastern edge of the Colorado Desert at the Yuma Crossing in 1780. An uprising by the Quechan the following year, however, resulted in the destruction settlement and the interruption of travel across the Colorado Desert. (5)

Soon after achieving independence from Spain, the Mexican government sought to reopen the route. As early as 1822, Indians were carrying messages between the Missions San Gabriel in Alta California and San Xavier del Bac. In 1823, Captain Jose Romero led an expedition west from Tucson, but difficulties with the Quechan beginning at the Yuma Crossing and continuing into the desert forced the Mexicans to turn south into Baja California. Romero's attempt to return to Tucson from San Gabriel in late 1823 also failed when the party ran short of water and forage. Disagreements between Romero and government officials delayed a second try until 1825. This time he was escorted across the Colorado Desert by Lieutenant of Engineers Romulado Pacheco. Lt. Pacheco then built and garrisoned a small adobe and stone fort at Laguna Chapala in the heart of the desert about 6 miles west of the present city of Imperial. An attack by the Kumeyaay in April 1826, however, forced the abandonment of the post and official closure of the Colorado Desert route once again. (6)

Although unofficial travel by traders from New Mexico and others across the Colorado Desert continued over the following two decades, the next crossing in force came during the Mexican War. General Stephen Watts Kearny and advance units of his Army of the West made a rigorous trek west from Yuma in 1846. Lieutenant William H. Emory in his narrative of the expedition reported that the soldiers proceeded southwest around the dunes to the well at Alamo Mocho, which he described as:

"What had been the channel of a stream, now overgrown with a few ill-conditioned mezquite, a large hole where persons had evidently dug for water. It was necessary to halt to rest our animals, and the time was occupied in deepening this hole, which after a long struggle, showed signs of water. An old champagne basket, used by one of the officers as a pannier, was lowered in the hole, to prevent the crumbling of the sand. After many efforts to keep out the caving sand, a basket-work of willow twigs effected the object, and much to the joy of all, the basket, which was now 15 or 20 feet below the surface, filled with water.” (7)

Lt. Emory continued that they followed a winding course, skirting the base of the dunes, and then proceeding northwest over, "...an immense level of clay detritus, hard and smooth as a bowling green. . .." They reached a salt lake (probably the "Big Laguna," one of the ponds caused by a flow in the New River) but the soldiers found no relief, as Lt. Emory noted: "As we approached the lake, the stench of dead animals... put to flight all hopes of our being able to use the water.” (8) From that point the column proceeded to Carrizo Creek, where it finally located water and a way out of the desert. Lt. Emory calculated that the soldiers had made the desert crossing of some 96 miles in 3 days. Although this was done in November, thereby missing the summer heat, the troops did suffer from lack of water and the difficulty of marching through sand. These contributed significantly to the fatigue of animals and men that plagued Gen. Kearny's command in its unfortunate encounter with Californio lancers at San Pasqual. In an ironic twist, later that year much the same route was followed in reverse by the defeated Mexican General Jose Castro in his flight from Alta California to Sonora.

In January 1847, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke and the Mormon Battalion crossed the Colorado Desert. They battled the region’s winter climate that produced heat during the day and frost at night. Cooke's command brought the first wagons across the desert and laid out a road west from Yuma, south of the dunes and up the western plain. Deviating slightly from Gen. Kearny's path, the Battalion went south of the salt lake before reaching Carrizo Creek and San Felipe Pass over the coastal mountains. The Mormons also located and opened or reopened wells and watering holes that would be used by travelers for decades. (9)

Following Cooke and the Mormon Battalion in late November, 1848 was a column of Dragoons under the command of Major Lawrence Pike Graham. These men had marched from Monterey in Mexico, and, after resting at the Colorado River, made a difficult crossing of the desert. Although the temperature did not pose a problem, the lack of water and forage did. The soldiers had to dig and clean out wells opened by Cooke the previous year, and the column was pretty well spent by the time it reached Carrizo Creek, "The mules were dropping dead in harness, their tongues swelling etc. and the men nearly as bad off for water.” (10)

The next rush of travelers, argonauts bound for the California gold fields, passed through the Colorado Desert in1849. The southern route to California by way of the Gila River and Colorado Desert may have been of lesser importance compared to the heavily traveled California Trail, but it did attract thousands of travelers through the early 1850s. Many of these were Mexicans following trails up from Sonora. Others came from the southeastern United States, while still others were pioneers willing to face the hardships of a desert crossing rather than risk the deadly snows of the Sierra Nevada that had trapped the Donner Party in 1846. (11)

The presence of so many travelers along the route had a definite impact on the desert. Whereas previous expeditions made the journey in isolation, during the Gold Rush, trails became relative highways. Companies of miners frequently encountered one another or ran across the remains of recently vacated campsites. The desert floor also became littered with articles abandoned when they either fell apart or proved too heavy or cumbersome for their weary owners. Broken wagons, furniture, articles of clothing, tools and even weapons left by the side of the road proved to be a bonanza for scavengers. The scene was one of devastation, as recorded by J. A. Durivage, a correspondent for the New Orleans Picayune: "upon a level plain, were two abandoned wagons, and literally covering the ground were. . fragments of harness, gun barrels, trunks, wearing apparel, barrels, casks, saws, bottles and quantities of articles too numerous to mention." (12)

Impromptu commerce blossomed as parties of travelers gathered at wells and watering places to barter for supplies or other less necessary items. Traders from the coast and Sonora drove horses and mules to the desert for sale to argonauts desperate to replace dead or lame animals. This brings up a less appealing aspect of the Colorado Desert migration, the toll it took on animals attempting the crossing. In addition to finding human detritus, travelers recounted seeing hundreds of beasts, pushed beyond the limits of their endurance by owners either anxious to get to the gold diggings before their neighbors or searching for the next water hole. William Chamberlin, writing in 1849, described it as, "a perfect Golgotha -- the bones of thousands of animals lie strewn about in every direction.” (13) Rotting carcasses fouled wells and created an awful stench, as Durivage noted: "The hot air was laden with the fetid smell of dead mules and horses, and on all sides misery and death seemed to prevail." (14) Often animals were left where they had fallen, still with their saddles, bridles or harnesses on. Passersby who spied outfits superior to their own had no compunction about helping themselves to the abandoned rigs. It was even reported that travelers displayed an unusual sense of humor by standing some of the stiffened creatures on all fours in a macabre, if static, parade across the desert floor. 15

The principal route taken by the argonauts left the upper Yuma Crossing, along the mesquite thickets of the Colorado River past Pilot Knob for a few miles before turning southwest into the Mexican desert. Their first goal, about 15 miles distant, was Cooke's Wells. Located some four miles below the border in the dry bed of the Alamo River, the wells had been developed by the Mormon Battalion just a few years earlier. Judge Benjamin Hayes, who traveled through the region in 1850 described the site:

The well is on the left side of the road, down a steep sandy bluff surrounded with the bones of mules that have gone there for water and died -- unable to reach it. Well partly covered with boards. A mule might easily fall into it. Water good, clear, except when much water taken from it. There is a wooden bucket there ready.... The smell from the well is strong of decayed animal matter. (16)

View San Diego and Colorado River 1850's Map (pdf)

A 22 - mile march reached the well at Alamo Mocho, a well-known watering place since Spanish times. Another long trek of 24 miles to the northwest was required to reach water at the Pozo Hondo (or deep well) until June 1849, when overlanders were greeted by the "miraculous" appearance of the New River. Caused by an overflow of the Colorado River into the lower desert in Mexico and then north to the Salton Sink, the New River resembled a slow moving stream, with several pools or "lagoons," It cut the distance from Alamo Mocho to water to 13 miles. In addition to serving as a source of water, overflows from the New River irrigated patches of grass providing badly needed grazing for horses and livestock. From there, travelers, now back in the United States, followed the New River to the "Big Laguna,” south of present-day Seeley The next march of 28 miles across barren, rocky desert brought them to Carrizo Creek near its confluence with Vallecito Creek. This spot was generally regarded as marking the end of the worst portion of the desert journey. Travelers bound for San Diego headed west over the mountains, while those going to Los Angeles followed Vallecito Creek northwestward to Palm Spring, Vallecito, San Felipe and Warner’s Ranch before crossing the Coast Range. (17)

With watering holes and routes fairly well known, and mostly reliable, the Colorado Desert, nonetheless, presented a challenge to those unused to dry country. Decisions to travel during the heat of the day rather than at night, when darkness might slow progress, not to spend time refreshing and repairing at the Colorado River before pushing on across the desert, or to forgo the extra supplies of water and forage that could impede the journey, placed many travelers in danger from dehydration and exhaustion. Sometimes inadequate preparations could invite disaster, as in 1850 when Samuel E. Chamberlain and his party of former members of scalp hunter John Glanton's gang found Cooke's Well choked with sand. A note indicated that water could be found by excavating down ten feet, but the group's failure to bring digging tools led to a most disagreeable and thirsty trek. Chamberlain's melodramatic account of that journey on the "Jornado del Muerto" mirrored the experience of many unprepared arognauts who attempted the desert crossing:

Away to the north the black mountains of California seemed to recede as I advanced. ... At noon we halted for two hours, then once more resumed our solitary way. I was getting weak, my heavy arms weighed me down like lead. I had drawn my waist belt tighter and tighter, until I was shaped like a wasp. On we went for hours, but the black mountains seemed as far off as ever. Long into the dark night we stumbled on until we sank exhausted on the sand. ... All day we kept on, lying down now and then, and then staggering on, trying to gain on those craggy peaks which always fled before us. (18)

In September 1849, Lieutenant Cave Johnson Couts of the 1st U. S. Dragoons, leading the escort for the United States-Mexico Boundary Survey, established an aid station called Camp Salvation on the New River at the border (today’s Calexico). Camp Salvation consisted of an emigrants' camp and a soldiers' camp, and offered some good grazing. The survey's commander, topographical engineer Lieutenant Amiel W. Whipple, noted that at its height, the site resembled an expansive tent village. Lt. Couts detailed a squad of troopers to maintain the station while he proceeded across the "Grand Sahara Desert of California," described as "no water, no grass, no nothing" to the Colorado River. There, he founded Camp Calhoun on the California side of the river near its confluence with the Gila. At Camp Calhoun, in addition to his military duties, Lt. Couts continued to distribute rations to a steady stream of hungry travelers from the Gila Trail. In December, he closed both Camp Calhoun and Camp Salvation and returned to San Diego. (19) Another aid station at Carrizo Creek was established late in 1849 under the authority of (now) Major William H. Emory. Operated by Agoston Harazthy, his son Attila, and Doctor. W. R. Kerr of San Diego, it lasted into the following year. (20)

Traffic through the Colorado Desert continued brisk in 1850, if the ferry receipts at the Yuma Crossing are any indication. Early that year, Dr. Able Lincoln claimed to have made $60,000 transporting some one hundred emigrants a day across the Colorado River at the rate of "$1.00 per man, $2.00 horse or mule." Soon after, John Glanton and his henchmen shoved Lincoln aside, appropriating the ferry operation for themselves. Within a short time they had banked $8,000 in San Diego. Their unlamented demise at the hands of the Quechan Indians in late April 1850, however, did not deter other entrepreneurs from later restarting the service. (21)

But it was not the same. After 1851, the Gold Rush began to wane, and with it travel along the Southern Route. Horse traders and livestock drovers still used the trail to drive herds from Texas and Mexico to California. The U.S. Army continued to send caravans of provisions from San Diego to its outpost Ft. Yuma, at least until 1852 when a reliable method of supply by ship and river steamer was established. The civilian travelers who crossed the Colorado Desert now tended not to be bands of prospectors with visions of gold dancing before their eyes, but rather the trains of individual families, moving west to begin businesses, farms or ranches in Southern California.

Of the thousands of emigrants who struggled into California by way of the Colorado Desert, only a handful had anything remotely positive to say about the region. The most outspoken of these was a Louisiana physician turned argonaut, Oliver M. Wozencraft. Unlike most of his fellow '49ers, Wozencraft's interest in the desert extended beyond just how to get across it in the least amount of time. While his traveling companions slept fitfully in the desert heat, he examined the soil, estimated distances and elevations, and dreamed. With Los Angeles County's surveyor Ebenezer Hadley, Wozencraft concocted a scheme to turn water from the Colorado River onto the lower desert. The project would open the region to irrigated agriculture and alleviate the, "great suffering...loss of human life, and a great loss of animals and other property," that he had observed while crossing the Colorado Desert. It also would relieve soldiers and civilians of the necessity of making, "an unauthorized encroachment on the soil of a government inimical to us," in order to travel between Yuma and the coast. (22)

Wozencraft persuaded California's legislature to grant him rights to the state's interest in the Colorado Desert and to petition the federal government to transfer much of the area to the state (and, not coincidentally, to his irrigation project). Although the state made Wozencraft its "agent" in Washington, D.C. for desert reclamation, he failed to convince a federal government to fund the work. n the final analysis, however, of all of the gold seekers on Colorado Desert trails, it was Wozencraft who had the greatest impact on the region. His ideas about tapping the Colorado River inspired others to investigate, and eventually develop, the irrigated empire of today's Imperial Valley. (23)

The coming of irrigation at the turn of the twentieth century marked the end of the frontier period in the Colorado Desert. Sand and creosote gave way to alfalfa and vegetables. Paved highways replaced Indian trails, emigrant routes and wagon roads. Some of the wells and watering holes served the new roadways, but others, such as Alamo Mocho, Cooke's Wells and Big Laguna, fell into disuse, their names all but forgotten. New place names dotted the landscape as more and more people arrived to farm and settle the towns of Imperial, EI Centro, Holtville, Calexico and Mexicali. Memories of the wasteland and the pioneers who had trekked across it in the "Days of '49" faded. The California leg of the southern route found itself transformed from the place of dread and challenge that Bayard Taylor had observed into a quaint tourist attraction -- "America's most fascinating desert, lying close about the fertile green acres of a modern valley of homes, only minutes from the comfort of sun porch and cool patios. " (24)

NOTES

1. Bayard Taylor, EI Dorado: Or Adventures in the Path of Empire, 8th ed. (New York: G. Putnam & Son, 1859), p. 47.

2. Pedro Font, "The Colorado Yumas in 1775," in The California Indians: A Sourcebook,

ed. R.[obert] Heizer and M. A. Whipple, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), p. 247;

Ralph L. Beals and Joseph A. Hester, Jr., "A New Ecological Typology of the California Indians," Ibid, p. 82;

M. S. Crowell, "At San Diego and the Gold Mines," Overland Monthly 5 (October 1870): 324;

and C. R. Orcutt, "The Colorado Desert," The West American Scientist 7 (October 1890): 57.

3. Herbert E. Bolton, "In the South San Joaquin Ahead of Garces," California Historical Quarterly 10 (September 1931): 211-219.

4. Richard F. Pourade, History of San Diego: The Explorers (San Diego: Union-Tribune Publishing Company, 1960), p. 58;

J. N. Bowman and Robert F. Heizer, Anza and the Northwest Frontier of New Spain

(Los Angeles: Southwest Museum, 1967), pp. 36, 39.

5. Clifford E. Trafzer, Yuma: Frontier Crossing of the Far Southwest (Wichita: Western Heritage Books, 1980), pp. 18-21.

6. Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California, Vol. II, 1801-1824 (San Francisco: The History Company, 1886), pp. 507-509;

Keld J. Reynolds, "Principal Actions of the California Junta de Fomento, 1825-1827," California Historical Quarterly 25 (December 1946): 364n; California Historical Landmarks (Sacramento: California Department of Parks and Recreation, 1982),

p. 32; and "A History of the Imperial Valley -- Part I," at //www.Imperial.cc.ca.us/Pioneers/history/htm

7. W.[illiam] H. Emory, Notes of a Military Reconnaissance from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri to San Diego,

in California, Including Part of the Arkansas, Del Norte, and Gila Rivers

(Washington, D.C.: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848), p. 141.

8. Ibid. p. 101.

9.David Bigler and Will Bagley, Army of Israel: Mormon Battalion Narratives

(Spokane: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2000), pp. 180-181.

10. Hemy F. Dobyns, ed. Hepah California! The Journal of Cave Johnson Couts from Monterey, Nuevo Leon,

Mexico to Los Angeles, California During the Years 1848-1849 (Tucson: Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society, 1961), pp. 82-83.

11. George M. Ellis, ed. Gold Rush Trails to San Diego and Los Angeles in 1849

(San Diego: San Diego Corral of Westerners, 1995), p. 9

12 "Durivage of the Picayune: A Journalist Reports," in Ellis, ed. Gold Rush Trails, p. 100.

13. "Lewisburg to Los Angeles in 1849: The Diary of William H. Chamberlin," in Ellis, ed. Gold Rush Trails, p. 49.

14. "Durivage of the Picayune," p. 100.

15. Richard F. Pourade, The History of San Diego: The Silver Dons

(San Diego: The Union-Tribune Publishing Company, 1963), p. 148.

16. Ellis, ed., Gold Rush Trails, p. 24.

17. Ibid. pp. 25-26.

18. Samuel E. Chamberlain, My Confession (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1956), pp. 291, 294-295.

19. Ben F. Dixon, Camp Salvation: First Citizens of Calexico, An Oasis on the Gold Rush Trail, 2nd ed.

(San Diego: Don Diego's Libreria, 1965), p.5; U. S. Congress, Senate, Report of the Secretary of War Communicating the Report of Lieutenant Whipple's Expedition from San Diego to the Colorado,

Ex. Doc. 19, 31st Cong., 2nd Sess., February 1, 1851,p.10; Lt Cave J. Couts to Major W.H. Emory,

Camp Calhoun, October 10, October 17, 1849, Bvt Major W. H. Emory to Lt C. J. Couts, Camp Riley,

October 25, October 29, 1849, Couts Papers, San Diego Historical Society Research Library.

20. Benjamin Hayes, Pioneer Notes from the Diaries of Judge Benjamin Hayes, 1849-1875

(Los Angeles: Privately Printed, 1929), p. 46; and Brian McGinty, Strong Wine: The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), p. 179.

21. Douglas D. Martin, Yuma Crossing (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1954), p. 140.

22. O.M. Wozencraft to Senate Public Lands Committee, in U.S. Congress, House, Colorado Desert,

House Report No. 87, 37th Cong., 2nd Sess., April 23, 1862, p. 24.

23. Donald J. Pisani, From the Family Farm to Agribusiness: The Irrigation Crusade in California and the West, 1850-1931

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), pp. 89-91.

24. "Imperial County, California: America's Winter Garden," 1947. pamphlet in the Ephemera Collection, California State Archives, Sacramento.