Wings of the Spirit: The Place of the California Condor Among Native Peoples of the Californias

John W. Foster

Senior State Archaeologist (Retired)

Introduction

In June 1579 a small sailing vessel made its way cautiously along the California coast. Francis Drake, destined to become one of the world's legendary sea captains, was looking for a place to careen his leaky vessel -- the Golden Hind. He had come halfway around the world, and was to complete his voyage by sailing across the Pacific and to England, but he desperately needed a place to make repairs.

As he approached the shore of this land never before seen by European eyes (assuming it was northern California), Drake's crew was surprised to see several canoes venturing out from shore. The descriptions of this event are sketchy, but it seems clear that the native in one canoe made a statement, perhaps a blessing, and then threw a black-feathered bundle onto the deck of Drake's ship. From its description, the feathers were probably from the California condor. Drake's reaction to this event is not recorded except that it's clear the Englishmen felt they were being worshiped as gods. In fact, they may have been perceived as ghosts, coming from the land of the dead. The first gift from native Californians was probably the feathers of a California condor, and a sign of mourning ritual.

This paper briefly summarizes how the California condor was incorporated into the cultures of the peoples of ancient California by considering archaeological remains, ceremonial activities and rock art depictions. I will present selected examples from southern California and the border region where possible, with the admittance that this treatment is very cursory at this point.

The California Condor

Who amongst us has not dreamed of soaring effortlessly over the landscape seeing everything in the daily lives of lowly earthbound pedestrians? With scarcely a wing flap, condors soar over the deserts to the seacoast, cresting the highest peaks and spanning the most foreboding terrain. Such is the perspective of the California condor and perhaps the key to its special place in many native cultures across the Californias.

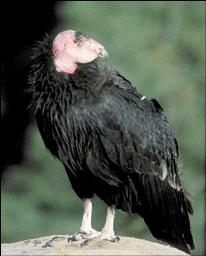

The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) is North America's largest bird. With a wingspan of nearly 10 feet and a weight of 20-22 pounds, it commands the skies. The genus, Gymnogyps, means "naked vulture," referring to the bird's bare head and neck. The name "condor" is derived from the Quechua "cuntur", a name for the Andean condor of South America (Snyder and Rea 1998:32). Adult California Condors have a yellow-orange head, black plumage set with brown on the back, and a white triangle patch under each wing. A whitish wing bar is also found on the upper surface of the wing. As juveniles, they have black heads and light neck ring.

Condors are carrion eaters. They lack the strong talons and beaks of hawks and eagles, and depend on finding carcasses for food. They have never been known to attack a living animal. They will commonly gorge themselves when feeding on a carcass and may go days without eating. Their keen eyesight helps them locate food. They sometimes travel up to 140 miles per day in search of a meal. They are also keen observers of other scavengers like Turkey Vultures and Golden Eagles, and Common Ravens.

In Pleistocene times, California condors were found across much of North America. In a fossil context, the remains of condors are absent after about 11,000 years ago. This corresponds to the decline in large Pleistocene fauna on which they presumably fed. In historic times, the birds ranged from British Columbia to Baja California Sur, but by 1940, they were seen only in southern California. By 1977, approximately 45 birds were known to exist in the wild and by 1985, only 9 birds remained. On April 19, 1987 the last free-flying California condor was captured from the wild and placed in captivity. At that time, only 27 condors remained alive, all in zoos. Successful captive breeding programs have increased the number so that reintroductions to three different sites in southern California and the Grand Canyon have been started. The world's population has been increased to approximately 200 birds.

Condor Reintroduction to Baja California

In October of 2002, six pioneer condors raised at the Los Angeles Zoo were flown to Baja California to begin the process of reintroduction. This project is an extraordinary collaboration among the Instituto Nacional de Ecologia, the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, the Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), the Zoological Society of San Diego, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the World Center for Birds of Prey in Boise, Idaho. Five young birds, under 3 years of age, were accompanied by "Xewe" an 11 year-old mentor bird who had known wild condor life. The five will be kept in a "condorminium" located in the Sierra San Pedro Mártir National Park and gradually habituated to wild living in the forests and canyons of Baja California. This marks the first time since 1930 that condors have been seen on the peninsula. It is hoped that the reintroduction of the California condor will spark an interest in bi-national conservation efforts within a proposed Biosphere Reserve.

Condors may have once been a common sight on the peninsula. Nelson's biological survey of 1906 observed a dozen condors feeding on a donkey carcass in the San Pedro Mártir range and noted they appeared "rather common" in the mountains (Nelson 1922:22). Within a decade, however, the population seriously declined throughout southern California and the peninsula. Invading gold minors apparently took a heavy toll. Condors were shot for their quills, which because of their lightness and unbreakable texture, were used to hold gold dust. These quills, worn around the neck, sold for $1.00 each (Snyder and Snyder 2000:47).

The California condor has long been a symbol of a wilderness heritage. It is surely the most impressive and majestic flying bird in North America and has figured prominently in the cultures of many North American natives. Perhaps its rebirth will signal a new understanding of the Native cultures that have known and revered it for centuries.

Flutes made from the wing bones of the California Condor have been found in

central California archaeological sites. These are incised with intricate designs.

Condor Remains in an Archaeological Context

Simons (1983) has summarized the occurrence of Pacific coast condor remains in an archaeological context. He reports on 13 sites between Oregon and California spanning a time range between approximately 10,000 years ago and early historic times (1983:470). The greatest number of individual California condor bones has been recovered at the "Five Mile Rapids" site in Oregon. There the unmodified remains of 63 birds were present.

In the delta and San Francisco bay region of California, a concentration of sites have yielded bones of the California condor. These include condor bone tube/whistles fashioned from the wing bones. Some have delicate incisement. In several cases these were recovered with human burials (Simons 1983:474). One site near Sacramento revealed the remains of a condor cape buried in a human grave. In several sites the condors themselves appear to have been intentionally buried. At the West Berkeley shell mound there was the suggestion of ritual condor burial.

Ceremonial Importance

There is scattered evidence of the ritual use of California condors through much of the Californias. The sacrifice of these birds seems to have been widespread. In general, this served to transfer the power of the bird sacrificed to those engaged in its ritual killing. Possibly the condor's association with the dead (being a carrion eater), led to its incorporation into mourning activities and renewal ceremonies. It may be noted that a similar ritual sacrifice of an Andean condor was observed in 1970 in Peru. Here a captured bird was ritually dispatched in public ceremony blending Inca and early Spanish traditions (Snyder and Snyder 2000:30-32).

California condor ceremonies have been lost in the mists of time, but there are adequate verbal accounts to provide some basis for understanding them. The first recorded account comes from October 8, 1769 when Fr. Juan Crespi observed a large stuffed condor in an Ohlone village near the present day Watsonville.

Many ceremonies throughout California involved dancers dressed in capes of condor skins or condor feather bands. The oldest extant example was collected by the Russian Illya Voznesenski in central California. It is preserved in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg. Condor ceremony took many forms. Central Miwok shamen acquired powers from condors that allowed them to suck supernatural poisons from their patients. Among the Maidu, condor capes were used by Moki or Kuksuyu dancers. These capes were sometimes combined with Golden Eagle feathers to exaggerate the wearer's height.

Perhaps the most detailed description of condor ceremony in southern California comes from the Panes (or bird) festival of the Luiseño. It was described by Friar Boscana of Mission San Juan Capistrano and by Friar Peyri of Mission San Luis Rey in the early 19th century. Similar ceremonies were held by the Gabrilieño, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay and Cupeño (Kroeber 1907; 2002).

The Panes (clearly a California condor from its description) is brought to the festival and placed upon an altar constructed for the purpose. The bird had been captured as a nestling, with condor nest sites being owned by the village. It was raised with great care until fully grown and selected for the sacrifice. Slowly, along with much crying and grimaces, the captive birds are killed by strangulation or pressing the heart. The bird's skin was removed in one piece and the flesh thrown on a fire. Skins and feathers were used to decorate venerated objects for the annual mourning ceremony. California condor skins were also used to make skirts that were retained as important ritual objects by their native owners (Bates et.al. 1993:41; Bates 1982). It should be noted that eagles were also sacrificed and some have argued (Geiger and Meighan 1976) that it was the Golden Eagle that was most powerful. Most experts have concluded that California condors held a unique place in the ceremonial life of California natives, and that eagles were used more commonly during the historic period as condor populations declined (Simons 1983, Bates et.al. 1993).

California condors could infuse humans with special powers. Vultures and condors, with their keen eyesight, were considered expert at finding lost objects. Among the Western Mono and Yokuts tribes, "money finders" wore full-length cloaks of condor feathers that reputedly enabled them to find lost valuables (Snyder and Snyder 2000:38). This power was extended to finding missing persons among condor shamen of the Chumash.

California condors also played a part in cosmic events. Among the Chumash, condors or eagles were sacrificed based on which celestial body was prominently visible at the time of the ceremony. Eagles were selected for rituals concerned with the Evening Star (Venus), while condors were chosen for rituals associated with the planet Mars (Hudson and Underhay 1978:88; Simons 1983).

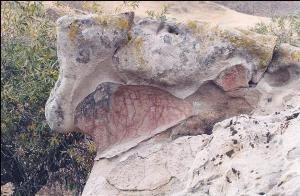

Condor Cave near Santa Barbara features a spectacular condor in flight.

It is painted over a bear-paw petroglyph. (Bill Hyder photo)

The site has been identified as a probable winter solstice observatory

from its orientation and designs (Hudson and Underhay 1978).

Several Chumash sites may show winged figures with anthropomorphic traits. These have been interpreted at Ven-195 as humans in condor or eagle dance regalia. Similar designs at Burro Flats may also be a blend of bird and human form within the context of shamanism and ritual (Gibson and Singer 1978, Hyder and Lee 1994, Lee and Horne 1978).

In Yokuts territory, a distinctive condor image has been recorded. It comes from Exeter Rocky Hill (CA-Tul-83) in Tulare County. In a shallow granite shelter formed from huge boulders, a giant figure is painted on the ceiling. It measures almost six feet in length and features well-defined feet and black and white patterned design in the outstretched wings.

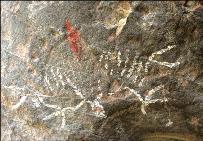

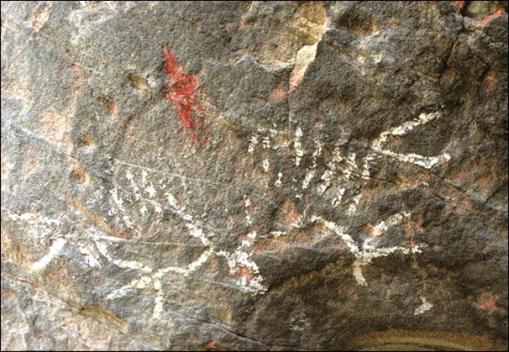

One of the more common forms of depicting large birds in painted rock art is with "raked" wings. This shows the wings extended with feathers down. Although not an exclusive habit, living California condors often adopt this pose when warming or drying their wings, thus it is possible to imagine it as a view born from actual observation.

Almost lost among the giant painted images of Cueva La Pintada in the Sierra de San Francisco, Baja California Sur are several black images with raked wings. Perhaps these represent the former aerial masters of these desert canyons and their feeding on the carcasses of other animals so prominently depicted. Recent studies imply that California condors may have derived much of their food from scavenging sea mammal remains along the coast. This may have made Baja California a favored land for these birds. Another rock art site called "La Pintada" is situated in the rugged coastal volcanic canyons between Guaymas and Hermosillo in Sonora. On a protected face within a narrow canyon, is a pictograph display in red, black and white. (Pictured below) Most of the images take a geometric form with shields, or perhaps turtle-designs being prominent.

Below, these black avian figures with "raked" wings may be cormorants, or perhaps condors. In the center is a familiar black image with raked wings. It is strikingly similar to other painted designs across the former range of the California condor.

Another rock art site called "La Pintada" is situated in the rugged

coastal volcanic canyons between Guaymas and Hermosillo in Sonora.

On a protected face within a narrow canyon, is a pictograph display in red, black and white.

Summary and Conclusions

In this paper we have soared briefly across the cultural landscape of the California condor, its archaeology, ceremonial significance and painted imagery. It is apparent that California condors held a special place in the lives and ceremonies of California natives. It was a revered creature, a master of the spirit, who gave power to humans for a variety of world renewal and cosmic purposes. It was associated with death and mourning as well as rebirth and renewal.

So as we enter a new century, the fate of the California condor hangs in the balance. Perhaps the condor colonizers of Baja California will help insure the continuation of the species. But, why should we care about the condor's survival? As the noted biologist Ken Brower pointed out, "When the Vultures watching your civilization begin dropping dead...it is time to pause and wonder" (Erlich et.al. 1988). Amen.

References Cited

Bates, Craig T.

1982 A Historical View of Southern Sierra Miwok Dance and Ceremony. Ms. on file at California State Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Bates, Craig T., Janet M. Hamber and Martha J. Lee

1993 The California Condor and the California Indians. American Indian Art 19 (1): 40-48.

Erlich, Paul R., David S. Dobkin and Darryl Wheye

1988 Conservation of the California Condor.

http://www.stanfordalumni.org/birdsite/text/essays/Conservation_Condor.html

Geiger, Maynard O.F.M. and Clement W. Meighan (eds.)

1976 As the Padres Saw Them: California Indian Life and Customs a Reported by the Franciscan Missionaries 1813-1815. Santa Barbara Mission Archive Library, Santa Barbara.

Gibson, Robert and Clay Singer

1978 Ven-195: Treasure House of Prehistoric Cave Art. IN: Four Rock Art Studies. C. William Clewlow, editor. Ballena Press Publications on North American Rock Art No. 1. pp. 45-64. Ballena Press. Socorro, New Mexico.

Grant, Campbell

1965 The Rock Paintings of the Chumash: A Study of a California Indian Culture.

Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Hudson, Travis and Ernest Underhay

1978 Crystals in the Sky: An Intellectual Odyssey Involving Chumash Astronomy, Cosmology and Rock Art.

Ballena Press and the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

Cooperative Publication. Santa Barbara, California.

Hyder, William D. and Georgia Lee

1994 The Shamanistic Tradition in Chumash Rock Art.

Kroeber, Alfred L.

1907 Indian Myths of South Central California. University of California Publications in American

Archaeology and Ethnology 4 (4). p. 220.

2002 San Luis Rey: A Mission Record of the California Indians (1811).

Lee, Georgia and S. Horne

1978 The Painted Rock site (SBa-502 and SBa-526): Sapaksi, the House of the Sun.

Journal of California Anthropology 5:216-224.

Nelson, Edward W.

1922 Lower California and Its Natural Resources. Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, Volume XVI. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C.

Simons, Dwight D.

1983 Interactions between California Condors and Humans in Far Western North America. IN: Vulture Biology and Management, Sanford R. Wilbur and Jerome A Jackson, eds. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Snyder, Noel F and Amadeo M. Rea

1998 California Condor. In: The Raptors of Arizona, Richard L. Glinski, ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Snyder, Noel and Helen Snyder

2000 The California Condor: A Saga of Natural History and Conservation. San Francisco: Academic Press.