ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE YARD OF CASA DE ESTUDILLO,

OLD TOWN SAN DIEGO STATE HISTORIC PARK

Erin Smith, Rachel Ruston and Michael Sampson

Southern Service Center

2009

Figure 2. West and South sides of Casa de Estudillo in

Old Town San Diego State Historic Park

According to State Parks Historian Victor Walsh, the Estudillo yard at the time the family resided there in the 19th century was a place for everyday work that held outdoor ovens, stable buildings and corral in the rear, and where gardening, adobe brick making, clothes cleaning, making cloth, horse grooming, and other chores took place. The above historic-period functions may have left archaeological “signatures” that we had hoped to detect during the 2007 and 2008 Southern Service Center archaeological investigations. The reader should see Victor Walsh’s (2004) article in the Journal of San Diego History for more historical information about Casa de Estudillo.

Casa de Estudillo was sold by José Guadalupe and Salvador Estudillo to John Spreckels, a wealthy businessman, in 1906; the Estudillo family had ceased residing there by the late 1870s. Wanting to restore the house as a tourist attraction, Spreckels’ company hired local architect Mrs. Hazel Wood Waterman, a protégée of noted San Diego architect Irving Gill, in 1908 to oversee the restoration; the restoration of Casa de Estudillo took place in 1909. [The reader may wish to read the book Daring to Dream, the Life of Hazel Wood Waterman by Sally Bullard Thornton (1987) for more details about Mrs. Waterman’s life.] Mrs. Waterman apparently took great care to create a well planned restoration that was faithful to the historic period, although, Waterman’s landscaping was apparently more elaborate than that used by the Estudillo family. Significantly for us, the 1909 restoration did affect the yard of Casa de Estudillo and the integrity of archaeological remains therein (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bricks drying for the 1909 restoration: vestiges of original

adobe in background. (Courtesy of San Diego Historical Society.)

Archaeological excavations were conducted by students from University of San Diego (USD) under the direction of Ray Brandes and James R. Moriarty (1976) in the backyard of Casa de Estudillo in October and November 1976. Initially, a waterline trench, measuring 18 inches wide, three feet deep, and 110 feet long, was excavated by the USD workers; that trench ran from the garden wall doorway on San Diego Avenue up to the northeastern corner of the yard where a garage/storage building stood. The 1937 Historic American Buildings Survey map of the site identifies this same building as “Tool House” (Figure 4). This corner of the Estudillo yard, located on Calhoun Street, was the intended location of a new State Parks restroom. The 1976 trench excavations yielded 61 fragmentary ceramic artifacts, 14 adobe tile fragments, 10 bottle glass fragments, two square nails, one bolt, 30 pieces of bone, and seven shellfish fragments.

Figure 4. Photograph of Tool House taken in 1966,

where 1976 and 2007 excavations took place.

(Courtesy of San Diego Historical Society)

The proposed location of a new restroom, situated in the northeastern corner of the Estudillo yard, was next examined by the USD archaeological team in November 1976. A garage/storage building, measuring approximately 28 feet by 20 feet, stood at this spot then, but was demolished just prior to the 1976 archaeological excavations. The latter building was apparently constructed soon after the 1909 Waterman restoration, as it does not appear on Waterman’s original restoration plans, but appears in photographs of the yard dated to 1910. The entire 28 foot by 20 foot area proposed for new construction was excavated by the USD crew. The restroom excavation showed a layer of sediments to a depth of 21 inches that was interpreted by Brandes and Moriarty as “fill materials.” An underlying 21 to 26 inches layer contained few artifacts except for “a few pieces of broken roof and floor tile.” Brandes and Moriarty (1976:25-26) hypothesized that the fill was placed in the Casa de Estudillo yard during the 1909 Waterman restoration to level out this area to aid in making it a garden. A total of 66 artifacts, including, two whole bottles, 11 bone fragments, and three shellfish pieces were recovered in the 1976 restroom block excavation.

At the request of local State Park staff, archaeologists from State Parks headquarters under the direction of Senior State Archaeologist D. L. Felton conducted archaeological excavations within the Casa de Estudillo yard plus one unit against the garden wall on the Casa de Pedrorena side in February and March 1989. Stated purposes of the 1989 archaeological and historical research consisted of (1) seeking physical evidence of historic structures and gaining an understanding of building history within the site, (2) seeking evidence of the historic grade, and, secondarily, (3) to seek evidence of historic features within the yard. Historic structures for which evidence were specifically sought included the building addition on the north wing, the so-called “adobe barn,” observed in 19th-century photographs (e.g., the 1869 Schiller photograph) and walls surrounding and within the Estudillo yard (Figure 5, below). An artifact-rich feature was uncovered along the north yard wall that dated between 1830 and 1850. The 1989 work revealed that the ca. 1909 construction grade lies from six inches to one foot below the present-day grade, and that a “substantial” wall foundation of river cobbles and mortar was employed in the 1909 Waterman restoration. According to Larry Felton, the 1989 excavations found neither clear evidence of the north wing addition seen in an 1869 photograph nor evidence of 19th century yard/garden walls. In addition to the cultural remains found along the walls, the 1989 State Parks excavations did uncover other cultural features including an east-west trending cobblestone foundation at a depth of about 1.2 feet below surface, a late-19th-century trash deposit lying at around 1.4 feet below surface, and a trash pit dating to the 1909 restoration situated at one foot to about 2.5 feet below surface. The collections resulting from the 1989 fieldwork are stored at the State Archaeological Collections Research Facility in West Sacramento under Accession Number P854. The soils and sediments encountered during the 1989 excavations differ greatly from those found in the 1976 USD excavations, which suggests Brandes and Moriarty’s interpretation of the stratigraphy may have been in error.

Figure 5. Base Map of Casa de Estudillo with locations of historic yard features

and 1976 excavations. Map created by Larry Felton, 1989.

A ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey of three transects within the 2007 project area, conducted by Dr. Mark Becker and Dr. Jerry Schaefer of ASM Affiliates, Inc. of Carlsbad, preceded the Southern Service Center excavation work in the Casa de Estudillo yard. The GPR instrument can potentially detect evidence of buried structural features and other human-made objects, such as building foundations, wells, graves, and others. Results of the GPR survey detected two “anomalies” of potential archaeological interest: one along the west side of the present restroom under the paver walkway and one at the southwest corner of the existing building. The GPR survey results helped us guide where to place our excavation units.

Figure 6. Overview of 2007 excavation grid, facing project east.

Photograph taken on November 11, 2007.

The 2007 State Parks excavations (Figure 6) showed no evidence of significant architectural remains and no evidence of buried landscape features (e.g., a well, a trash pit, or a privy). But, a total of 1,263 artifacts weighing 748.07 oz. was recovered during the 2007 excavations, from five units and two shovel test pits placed around the old restroom; these items have been cataloged under State Parks Accession P1554. This yield of artifacts seemed remarkably good given the considerable amount of disturbance observed in all the 2007 excavation units. The sources of previous ground disturbance in our project area included the 1909 restoration, the 1976 restroom construction, the previous USD excavation project, a 1996 remodel of the restroom, and miscellaneous landscaping work since 1910. Also, the 2007 excavations showed no stratigraphic evidence to support the Brandes and Moriarty hypothesis that large amounts of fill had been imported onto the Estudillo backyard during the 1909 restoration.

The 2008 construction monitoring resulted in the recovery of 220 artifacts weighing 260.02 oz.; this collection is cataloged under Accession Number P1614 (Ruston 2009). Artifacts ranging in age from the Estudillo family residency up to the late 20th century were recovered during the construction monitoring. The Estudillo family story is reflected in the numerous early-19th century ceramics recovered during the monitoring, as well as butchered bone and shellfish remains. The variety of glass items found at the site during 2008 construction grading is attributed to the early-20th century use of the Casa de Estudillo, in particular, as a house museum dedicated to the fictional Ramona. Latter-day construction materials found during monitoring provide further evidence of the disturbances identified during the 2007 excavations.

A total of 1,135 artifacts weighing 263.46 oz. was recovered during the 1976 USD project; the 1976 collection was recataloged by us under Accession Number P1576. A number of intriguing artifacts were identified in the 1976 Casa de Estudillo collections by the present writers during our reanalysis of their collection. It should be noted that other portions of the 1976 collection are believed to exist due to the reference to pieces in A Guide to Artifacts of California by Ray Brandes and James R. Moriarty (1977); these particular items are missing from the 1976 USD collection currently curated at California State Parks.

The artifacts from the 1976, 2007, and 2008 collections have been cataloged by function and attributes employing categories of “activity groups” as defined by Steve Van Wormer in a 1996 article entitled Revealing Cultural, Status, and Ethnic Differences Through Historic Artifact Analysis (Van Wormer 1996). Van Wormer’s activity group classification system has been employed at many historic sites in San Diego County, so it seemed appropriate to use it here. Consumer Items proved to be the most abundant in number of items and total weight in both the 1976 and 2007 collections, while Household Items, Building Materials and Architecture, and Kitchen were slightly less numerous. The 2008 construction monitoring project yielded a larger amount of building materials and architecture, by weight, than the 1976 and 2007 excavations, while about 32% (by weight) of the 2008 finds fell into the Consumer Item, Household, and Kitchen activity groups. All other “activity group” categories were either not represented in the three collections or were negligible in count and weight. Such findings would be expected in a residential site such Casa de Estudillo. Industrial sites, for example, will manifest few or no consumer, household, and kitchen items, but, relatively large numbers of objects fitting into the building materials, forge materials, hardware, tools, and machinery activity groups. The higher amount of building material/architecture items in the 2008 construction monitoring can largely be attributed to remnant modern-day construction materials originating from park maintenance activities and a 1996 restroom remodel by park staff.

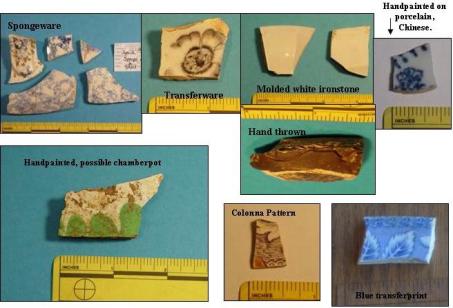

Figure 7. Selected ceramics recovered during 2008 construction monitoring.

A surprising and noteworthy variety of ceramic types were recovered from the 1976 and 2007 excavations and the 2008 monitoring work, albeit in a fragmentary condition (Figure 7, Table 1, below). A significant number of the transfer print patterns date in the early to mid-19th century range, for example, Scroll Fond Border, Non Pariel, Sirius, and Corinth, when the Estudillo family would have occupied the adobe. Hand painted ceramics of this same era were also present in the artifact collections, that included sprig motifs, banded rims, and sponge ware. Majolica, Willow ware, Mocha ware, Export China, Flow Blue ware, and white ware are also represented in the three collections from Casa de Estudillo. We thank local ceramic expert Susan Walter for her generous assistance with the identification of the latter ceramic assemblage. We were pleasantly surprised to find a small number of Spanish/Mexican style ceramic pieces in the 1976 and 2007 Estudillo collections. With the kind assistance of Dr. Jack Williams, we were able to identify some of the hand painted ceramics as Brunida de Tonala ware that dates to ca. post-1834. Most of the ceramic items from the 1976 and the 2007 excavations and the 2008 construction monitoring then range in date from 1835 to 1849, and reflect use by the Estudillo family. The variety of patterns and the stylishness of the ceramics are a clear indication of the relatively elevated economic status the Estudillo family enjoyed in historic Old Town. Few other materials recovered from the 1976, 2007, and 2008 work in the backyard of the Casa de Estudillo can be reliably dated to the time of the Estudillo family’s residency.

Table 1. Selected ceramic patterns identified from 1976 and 2007 collections at Casa de Estudillo.

*Patterns identified with ceramic sherd from Jolly Boy, which included the words “Abbey” and “Enoche.” Identical pattern compared with the Sacramento type collection identified as Charles Meigh, and does not have marks.

The 1976 and 2007 projects at Casa de Estudillo produced a small amount of artifactual evidence of prehistoric or historic-period Native American occupation, including, debitage, five manos, and pieces of aboriginal ceramics. According to Historian Victor Walsh (2004:2), local Indian people built Casa de Estudillo. It is known that a sizable number of Indian people worked as household servants within Old Town San Diego in the nineteenth century, including, the Estudillo household, and thus Indian people played an important economic role in 19th century Old Town San Diego (Farris 2006; Sampson and Bradeen 2006; Walsh 2004:2).

Figure 8. Archaeology work in progress at Unit S30-35/E-10-15, with M. Buxton

excavating and M. Sampson talking to park visitors. Photo taken November 2007.

One rewarding aspect of the 2007 project for us was the opportunity to discuss our work every day with the general public, including, the 4th Grade school kids who come to Old Town (Figure 8). The many people who stopped to view our work in progress seemed to enjoy learning about archaeology by first-hand observation. For many of these park visitors, our Casa de Estudillo work may be their only experience with the work of archaeologists. A report for the 2007 and 2008 Southern Service Center work at Casa de Estudillo has been placed on file at various State Parks offices.

REFERENCES CITED AND SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, William Hampton

2002

Machine Cut Nails and Wire Nails: American Production and Use for Dating 19th -

Century and Early-20th-Century Sites. Historical Archaeology 36(4):66-88.

Allen, Rebecca

1998

Native Americans at Mission Santa Cruz, 1791-1834, Interpreting the

Archaeological Record. Perspectives in California Archaeology 5.

University of California, Los Angeles.

Barber, Edwin Atlee

1904

Marks of American Potters. Cracker Barrel Press, Southampton, N.Y.

Brandes, Ray and James Robert Moriarty, III

1973

Report of the Archaeological and Historical Investigations of the Site of the Casa

Juan de Rodriguez, Old Town State Park, San Diego, Report on file

California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

1976

Historical/Archaeological Survey of the Estudillo House Patio, Restroom Site and

Utilities Trench, Old Town State Park, San Diego, California. Report on file

California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

1977

A Guide to Artifacts of California. University of California, San Diego.

Manuscript on file California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

California Department of Parks and Recreation

1977

Old Town San Diego State Historic Park Resource Management Plan,

General Development Plan. California Department of Parks and Recreation,

Sacramento.

Carrico, Richard L.

1986

Before the Strangers: American Indians in San Diego at the Dawn of Contact In

The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Local Native Americans,

pp.5-12. Cabrillo Historical Association, San Diego, California.

Carrico, Richard L., Kathleen Crawford and Joyce Clevenger

1991

An Archaeological Program of Monitoring, Testing, and an Evaluation of

Dodson’s Corner, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park, San Diego, California.

Report on file, California State Parks, San Diego.

Castillo, Edward. D.

1989

The Native Response to the Colonization of Alta California. In Columbian Consequences,

Volume 1, edited by David Hurst Thomas, pp. 349-364. Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

Clevenger, Joyce M., Kathleen Crawford, and Richard L. Carrico

1994

An Archaeological Program of Monitoring, Testing, and an Evaluation of

Dodson’s Corner, Old Town State Historic Park, San Diego, California.

Report on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Davis, Kathleen E.

1992

Old Town San Diego State Historic Park Old Town Light Rail Transit Extension Phase I,

Historical Background. Report on file, Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Drucker, Philip.

1937

Culture Element Distributions V: Southern California. University of California

Anthropological Records 1(1):1-52.

Elsasser, Albert B.

1978

Basketry. In California, pp. 626-641. Handbook of North American Indians,

Volume 8, edited by Robert F. Heizer, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Ezell, Paul

1973

The Search for the Seeley Stable. Report on file, California Department of

Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Ezell, Paul and Greta Ezell

1987

Cosoy, First Spanish Stop in Alta California. In Brand Book Number 8, San Diego

Corral of the Westerners, Twentieth Anniversary Edition, edited by Clifford M. Graves

and the Editorial Board, pp. 119-134. San Diego Corral of the Westerners, San Diego.

Farris, Glenn

2006

Peopling the Pueblo: Presidial Soldiers, Indian Servants and Foreigners in

Old San Diego. Presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference,

January 13, 2006, as a part of a symposium entitled “Mexicans, Indians and Extranjeros

in San Diego, 1820-1850.” Report available on State Parks Website:

www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24150. Accessed August 2008.

Felton, Larry

1989a

Old Town San Diego SHP Research Project Proposed Archaeological Testing Program,

Manuscript on file, California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

1989b

Field Notes for 1989 excavations at Casa de Estudillo in Old Town San Diego

State Historic Park. Manuscript on file, Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

2006

Mexican-Republic Era San Diego: An Archaeological Perspective. Presented at the

Society for Historical Archaeology Conference, January 13, 2006, as a part of a

symposium entitled “Mexicans, Indians and Extranjeros in San Diego, 1820-1850.”

Report available on State Parks Website: www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24150.

Accessed August 2008.

Felton, Larry and Glenn Farris

1997

Archaeological Treatment Plan for the Entrance Redevelopment Project,

Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Manuscript on file, California

Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Felton, David L. and Ron Quinn

1991

Architectural, Historical and Archeological Assessments of the Pedrorena-

Altamirano Adobe, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Manuscript on file,

California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Fetzer, Leland

2002

A Good Camp: Gold Mines of Julian and the Cuyamacas.

Sunbelt Publications, San Diego.

2006

Governor Robert W. Waterman, Waldo Waterman, and the Stonewall Mine,

1886-1891. The Journal of San Diego History 52(132): 44-61.

Fike, Richard

1987

The Bottle Book: A Comprehensive Guide to Historic Embossed Medicine Bottles.

Gibbs M. Smith, Salt Lake City.

Flower, Ike and Roth

1982

Archaeological Investigations at Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. 3 volumes.

Report on file, Cultural Resource Management Unit, California Department of

Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Fontana, Bernard L. and J. Cameron Greenleaf

1962

Johnny Ward’s Ranch: a Study in Historical Archaeology. The Kiva 28 (1-2):1-115.

Gates Jr., William C. and Dana E. Ormerod

1982

The East Liverpool Pottery District: Identification of Manufacturers and Marks.

Historical Archaeology Journal of the Society for Historical Archaeology 16 (1-2):1-358.

Godden, Geoffrey A.

1964

Encyclopaedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks. Bonanza Books, New York.

Gurcke, Karl

1987

Bricks and Brickmaking: A Handbook for Historical Archaeology.

University of Idaho Press, Moscow, Idaho.

Hanowell, B. Dalton Oliver

2006

A Ceramic Myriad: Mexican Domesticity and Utility in Old Town San Diego.

Article available on State Parks Website: www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24150.

Accessed March 2009.

Hector, Susan

2003

The Archaeology of the Casa de Bandini and the Casa de Pico Motor Hotel

(Bazaar del Mundo), Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Report on file,

California State Parks Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Hedges, Ken

1975

Notes on the Kumeyaay: A Problem of Identification. Journal of

California Anthropology 2(1):71-83.

Helmich, Mary A. and Richard D. Clark

1991

Interpretive Program, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Volume II:

Site Recommendations. California Department of Parks and Recreation,

Sacramento.

Henrywood, R. K. and A. W. Coysh

1989

The Dictionary of Blue and White Printed Pottery 1780-1880 Volume 2.

Antique Collector’s Club, Suffolk, England.

Hicks, Fredric Noble

1963

Ecological Aspects of Aboriginal Culture in the Western Yuman Area.

Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Anthropology,

University of California, Los Angeles.

Jordan, Stacey and Richard L. Carrico

2006

Cultural Resources Test and Evaluation for the Grease Trap and

Interceptor Installation Project (CA-SDI-17860, CA-SDI-17861, CA-SDI-17862),

Bazaar del Mundo, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park,

San Diego, California. Mooney/Jones & Stokes, San Diego.

Kovel, Ralph and Terry Kovel

1974

The Kovel’s Collector’s Guide to American Art Pottery. Crown Publishers,

New York.

Kroeber, Alfred L.

1970

Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 78.

Kupel, Douglas E.

1982

The Calhoun Street Parking Lot: A Historical and Archaeological Investigation

of Block 408 Old San Diego. Report on file, California

Department of Transportation, San Diego.

Larrabee, Edward McM.

1961

Archaeological Exploration of the Court House Building and Square,

Appomattox Court House National Historic Park. Manuscript on file,

Mid-Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, Philadelphia.

Lockhart, Bill

2006

The Color Purple: Dating Solarized Amethyst Container Glass.

Historical Archaeology 40(2):45-56

Luberski, Alexandra Helen

1984

Governor Robert Whitney Waterman, 1887-1891: California’s Forgotten Progressive.

MA thesis, Department of History, San Diego State University.

Luberski, Alexandra and Peter D. Schulz

1987

Report of Architectural Features, Courthouse Site, Old Town San Diego S.H.P.

California State Parks, Sacramento.

Luomala, Katherine

1978

Tipai and Ipai. In California, pp.592-609. Handbook of North American Indians,

Volume 8, edited by Robert F. Heizer, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Munsey, Cecil

1970

The Illustrated Guide to Collecting Bottles. Hawthorn Books, Inc., New York.

Nelson, Lee H.

1968

Nail Chronology as an Aid to Dating Old Buildings. American Association for

State and Local History Technical Leaflet 48

Philbin, Tom

1978 T

he Encyclopedia of Hardware. Hawthorn Books, Inc., New York.

Phillips, Roxana L., Carolyn E. Kyle, Kathleen Flanigan and Susan Arter

1998

Historical/Archaeological Test of the Former Site of the Casa de Aguirre,

San Diego, California. Gallegos and Associates, Carlsbad.

Rock, James T.

1984

Cans in the Countryside. Historical Archaeology 18(2):97-111.

Roenke, Karl G.

1978

Flat Glass: Its Use as a Dating Tool for Nineteenth Century Archaeological

Sites in the Pacific Northwest and Elsewhere. Northwest Anthropological

Research Notes, Memoir No. 4.

Rogers, Malcom J.

1936 Yuman Pottery Making. San Diego Museum Papers, No. 2.

Ballena Press, Ramona, California.

Roth, Linda

1982

Archaeological Investigations at Old Town San Diego State Historic Park, Volume I:

Historical Research and Field Investigation. Flower, Ike and Roth, San Diego.

1983

Trench Monitoring, Bazaar del Mundo, Old Town San Diego State Historic Park.

Manuscript on file Old Town San Diego State Historic Park.

1984

Trench Monitoring – Hamburguesa Restaurant- Old Town State Historic Park.

Manuscript on file Old Town San Diego State Historic Park.

1988

Sewer Trench/Wall Footing Monitoring – Bazaar del Mundo, Old Town

San Diego State Historic Park; Site of Casa de Pico, Portion of Lot 2, Block 426 (44).

Roth and Associates, San Diego.

Roth, Linda and Judy Berryman

1984

Casa de Rodriguez Archaeological Investigations to the South of

Racine and Laramie Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Report on file,

California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Ruston, Rachel

2009

Appendix F: Results and Summary of Archaeological Monitoring at Casa de Estudillo

during the Removal of Comfort Station #2 in Archaeological Findings for the

Comfort Station #2 Replacement Project, Old Town San Diego SHP by Erin Smith,

Michael Sampson and Rachel Ruston. California State Parks, San Diego.

Sampson, Michael P. and Jill H. Bradeen

2006

Historic-Period Lithic Technologies in Old Town San Diego. Presented at the

Society for Historical Archaeology Conference, January 13, 2006,

as a part of a symposium entitled “Mexicans, Indians and

Extranjeros in San Diego, 1820-1850.” Article available on website:

www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24150. Accessed March 2009.

Schaefer, Jerry, Drew Pallette and Stephen Van Wormer

1993

Appendix F to the North Metro Interceptor Sewer Project, Cultural Resources

Technical Report. Cultural Resources Evaluation for the Proposed North Metro

Interceptor Sewer Project, San Diego. City of San Diego, San Diego.

Schulz, Peter D.

1982

Archeological Investigations in Old Town San Diego, Spring 1982:

Architectural Features and Interpretations. Report on file, Department of

Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

1986

Archaeological Evidence for Early Bone Lime Production in Old Town San Diego.

Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 23(2):52-58.

Schulz, Peter D., Ronald Quinn and Scott Fulmer

1987

Archaeological Investigations at the Rose-Robinson Site, Old Town San Diego

Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 23 (2):1-51.

Shipek, Florence Connelly

1970

The Autobiography of Delfina Cuero: A Diegueño Indian. Malki Museum Press,

Banning, California.

1981

A Native American Adaptation to Drought: The Kumeyaay As Seen in the

San Diego Mission Records 1770-1798. Ethnohistory 28(4):295-312.

1986

Impact of Europeans upon the Kumeyaay. In The Impact of European Exploration

and Settlement on Local Native Americans, pp.13-25.

Cabrillo Historical Association, San Diego, California.

Shipley, William F.

1978

Native Languages of California. In California, pp.80-90. Handbook of

North American Indians, Volume 8, edited by R.F. Heizer,

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Silliman, Stephen

2003

Using a Rock in a Hard Place: Native-American Lithic Practices in Colonial California.

In Stone Tool Traditions in the Contact Era, edited by Charles R. Cobb, pp. 127-150.

University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Smith, Erin, Michael Sampson and Rachel Ruston

2009

Archaeological Findings for the Comfort Station #2 Replacement Project,

Old Town San Diego SHP. California State Parks, San Diego.

Snyder, Jeffrey

1997

Romantic Staffordshire Ceramics. Shiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA.

Spier, L.

1923

Southern Diegueño Customs. University of California Publications

in American Archaeology and Ethnology 20(16):297-358.

Teague, George A.

1979

Reward Mine and Associated Sites, Historical Archaeology on the

Papago Reservation. Western Archaeological Center Publications

in Anthropology No. 11.

Thornton, Sally Bullard

1987

Daring to Dream: The Life of Hazel Wood Waterman.

San Diego Historical Society, San Diego.

Toulouse, Julian Harrison

1971

Bottle Makers and Their Marks. Thomas Nelson, New York.

Van Wormer, Stephen R.

1996

Revealing Cultural Status and Ethnic Differences Through Historic

Artifact Analysis. In Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology,

Volume 9: 310-323.

Van Wormer, Stephen R. and Victor A. Walsh

2005

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form. Manuscript on file,

California Department of Parks and Recreation, San Diego.

Vogel, Michael

1995

In Up Against the Wall: An Archaeological Field Guide to Bricks in Western New York. <http//www.buffaloah.com/a/DCTNRY/mat/brk/brickyda.html>.

Accessed January 25, 2008.

Walsh, Victor A.

2004

Una Casa Del Pueblo: A Town House of Old San Diego.

The Journal of San Diego History 50 (1 & 2):1-16.